At the dawn of former President Donald Trump’s administration, government employees and contractors in need of security clearances could wait years for approval. Federal agencies stared down a backlog of 700,000 clearance investigations starting in 2017.

For one former senior-level State Department employee, who is a person of color, they waited more than two years to get approved for a top-secret clearance.

When the Trump administration arrived, many new Trump officials received “interim security clearances” because they didn’t initially meet standard security requirements, the former employee told Raw Story. This contributed to a screening backlog.

“With Trump it was a mixture of business with foreign governments, a lot of internal exchanges or engagements that needed more explanation, so there were a lot of outstanding issues that needed further explanation, and it just didn't happen,” said the former employee, who spoke on the condition of anonymity due to employment concerns.

But it wasn’t just clearing Trump’s appointees that created the delays — not even close. Problems started in the years prior and continued on in subsequent years, according to national security experts. Among them: the ending of a contract with a background investigations company, USIS, and the 2015 cybersecurity breach of the Office of Personnel Management, which compromised the background investigation records of more than 20 million federal employees and contractors.

That backlog was largely responsible for prompting the need for a multi-agency reform effort around personnel vetting, dubbed Trusted Workforce 2.0, and the related policy changes intended to streamline investigative processes, said Viet Tran, a spokesperson for Office of Personnel Management.

Around that time, in 2018, the Government Accountability Office first put the personnel vetting process on its “high-risk” list of areas of the government in urgent need of transformation or susceptible to waste, fraud, abuse or mismanagement.

The reasons: IT system issues, a lack of performance evaluation throughout the process and slow processing times, said Alissa Czyz, director of defense capabilities and management at the Government Accountability Office.

Five years later, personnel challenges remain in the security clearance process, along with technological issues in terms of tracking and vetting cleared personnel, Raw Story revealed in its three-part “Losing Track” investigation. (Read Part I and Part II here.)

“It was a number of issues that led us to put it on our high-risk list back in 2018,” Czyz said. “It's still on there today.”

By December 2021, GAO expressed numerous concerns, according to a report based on an investigation into Trusted Workforce 2.0’s security vetting process.

There was a lack of assessment measures of agencies’ continuous vetting processes. Deficiencies with strategic workforce planning were endemic. Best practice guidelines for the software development of the National Background Investigation Services (NBIS) weren’t being followed.

A year later, Congress passed a law requiring the Office of the Director of National Intelligence to develop measures to assess the performance of personnel vetting. The office says it is working on “implementing metric collection that is going to be required for every department and agency,” said Mark Frownfelter, assistant director for the Special Security Directorate within the National Counterintelligence and Security Center at the Office of the Director of National Intelligence.

“It’s an incredibly important process to have folks that come in and work for the federal government properly vetted, especially those that have access to highly classified information. It's really critical,” Czyz said. “We have seen progress. We're optimistic with some of the modernization efforts here too, but work remains in the area, so it's on our high-risk list so we can continue to monitor and hopefully help those agencies get there with the process.”

Why can extremists get cleared but others can’t?

Even as the National Background Investigation Services (NBIS) and the practice of continuous vetting are poised to catch more potentially bad actors from within, such as right-wing extremists and others who might compromise government secrets, potentially dangerous people can still get security clearances.

As a part of the clearance vetting process, applicants submit references who can speak to their character at different times of their lives. Take Jack Teixeira, the 21-year-old airman who leaked classified defense documents. He allegedly spoke about violence, shared distrust of the government and expressed racist beliefs, The Washington Post reported.

So why didn’t a red flag come up during his vetting process?

“I don't think he would have volunteered someone to vouch for him who wouldn't have seen his conservatism and the things that his Discord buddies were highlighting,” said Kristopher Goldsmith, a former forward observer in the Army and CEO of Task Force Butler Institute, a nonprofit that targets extremist organizations.

“He loves guns. He's Christian. He's conservative. I don't think that anyone who saw that side of him would have thought that he shouldn't get a clearance,” Goldsmith said.

Earlier this month, 65 Democrats in Congress sent a letter to the Department of Homeland Security inquiring about its efforts to weed out domestic extremists based on reports showing that more than 300 current or former Department of Homeland Security employees were members of the right-wing Oath Keepers or working with other conservative militia groups, The Washington Post reported.

ALSO READ: Neo-Nazi Marine Corps vet accused of plotting terror attack possessed classified military materials: sources

Meanwhile, on the other end of the spectrum, some people up for security clearances may experience increased scrutiny during the vetting process due to their ties to foreign countries, which is the source of many questions on what’s known as Standard Form 86, a 136-page document that asks numerous questions of an applicant seeking a security clearance on topics like employment history, family ties, foreign travel, residences, criminal history and drug use.

“The problem is when you come in as a person with ties to a foreign jurisdiction, even though it says you can be a dual citizen, you really can't,” said Dan Meyer, partner at law firm Tully Rinckey PLLC’s Washington, D.C. office and a former Navy communications security officer who used to process security clearances. “I know what the regulation says, but everybody's queasy about somebody who hasn't renounced the other jurisdiction.”

Unlike Teixeira and Jordan Duncan, a jailed neo-Nazi who Raw Story revealed had stored top-secret classified information on his computer, members of the Asian American and Middle Eastern communities often find themselves under greater scrutiny if they have ties to other countries, especially China, said the former senior-level State Department employee.

LinkedIn photo of Jordan Duncan, a Marine Corps veteran whom the government alleges had classified military materials on his hard drive.assets.rebelmouse.io

LinkedIn photo of Jordan Duncan, a Marine Corps veteran whom the government alleges had classified military materials on his hard drive.assets.rebelmouse.io“There are national security implications because we need talent in place in the era of strategic competition,” said the former senior-level State Department employee. “Then you see extremists get them. The process is imperfect. There are some flaws.”

Meyer said that individuals seeking security clearances with the government need to cut ties with foreign countries by selling foreign property and closing any bank accounts in other countries in order to be approved for clearances.

“If you have relatives in a foreign country, you have to be able to tell security, and tell security convincingly, that if … somebody said they're gonna kill your mother unless your hand over the classified information — and they can do that because she's still living in Islamabad — then you have to tell security convincingly that you would let your mother go,” Meyer said. “You would let your mother die, rather than betray the secrets of the United States. I've had a couple of clients successfully do that.”

Patrick Eddington, a senior fellow in homeland security and civil liberties at the libertarian think tank, the Cato Institute, said the State Department and FBI’s Post-Adjudication Risk Management (Parm) Program, which requires more frequent interviews and increased scrutiny of certain individuals in the program, unfairly targets Chinese Americans.

Even though the Office of the Director of National Intelligence released a report last year that said the People's Republic of China does not prioritize targeting Chinese Americans in the intelligence community, and employment decisions cannot be made based on the “ethnic or racial background of any U.S. person,” Eddington said a number of Chinese Americans are still being denied the opportunity to work for the government out of alleged concerns that they might be recruitment targets for Chinese intelligence.

“Chinese Americans are being discriminated against in their background investigations and readjudication investigations and even actual assignments where they could potentially be sent because of this kind of nonsense,” Eddington said.

But Frownfelter said eliminating bias in the vetting process is an area the Office of the Director of National Intelligence is “passionate” about. The office has examined its training standards and introduced “more robust cultural competency training for investigators and the adjudicators.”

The office has also met with groups that have expressed concerns about bias in the vetting process, including the LGBTQ+, Chinese American and other minority communities.

Part of those meetings includes discussing that investigating foreign ties is a standard part of the vetting process that needs to be investigated, and the office recognizes that there’s a difference between validating this standard information versus “unfair or lack of equity in the treatment of them going through the process,” Frownfelter said.

Another group that often does not get security clearances but could benefit from them for their jobs is congressional staffers, said Lee Tien, senior staff attorney at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, a nonprofit digital rights group.

“It’s appalling how easily the rules and the clearance processes … they can manipulate that, configure that in a way to lessen scrutiny,” Tien said.

A lack of high-skilled talent in counterintelligence

While the National Background Investigation Services (NBIS) automates much of the continuous vetting process, are there still enough high-skilled employees to do the work of vetting cleared personnel?

Robert Sanders, distinguished lecturer in the national security department at the University of New Haven and former Navy JAG captain, says no as he observed a shrinking pool of highly skilled national security talent while he worked for the government until 2018 — which included individuals who conduct security clearance investigations.

“It’s great to have new initiatives that allow for greater scrutiny of individual clearances, but you have to have enough people on the side to do the scrutiny,” Sanders said. “It may look like you are being more effective as you pass more paper through the mill or more people over the bridge, but are you getting the same quality in the process that you want?”

Meyer said the national security talent pool isn’t declining, but there’s long been challenges with employing quality talent in the counterintelligence space.

“Counterintelligence has always been the misfit sibling in the pack,” said Meyer, who also formerly worked for the U.S. Department of Defense Inspector General. “Your spies got the highest accolades. Your analysts were really valued, and then when you got to counterintelligence, that was where your problem children went to spend their careers.”

Frownfelter said he has observed the Defense Counterintelligence and Security Agency hire a lot of investigators in response to the backlog.

“If we had another 9/11 and the government all of a sudden had to hire thousands and thousands of employees very quickly, you could see this become an issue, but I think where we are now in this environment with the steady state, I think we're in good shape with investigators, adjudicators and even polygraph examiners,” Frownfelter said.

ALSO READ: Feds banned this violent J6er from nuclear plants — but they still haven’t arrested him

The backlog has vastly improved from 2017, now down to a “steady state” of 200,000, which is manageable considering the Defense Counterintelligence and Security Agency and the Department of Justice together receive 10,000 new requests a day, said Royal Reff, a spokesperson for the Defense Counterintelligence and Security Agency.

With continuous vetting, rather than reinvestigating employees with security clearances every five to 10 years, the new system prompts automatic database checks in areas such as public records, credit, financial activity and foreign travel for existing cleared personnel. If anything gets flagged, an investigator will take a look and might conduct more monitoring, Czyz said.

“There is really great potential to catch some situations in more real-time than the current process allows for now. When that gets fully implemented, that will be really an important modernization of the process,” Czyz said.

Still, Joe Ferguson, co-director of the National Security and Civil Rights Program at Loyola University Chicago, said resources frequently get diverted from background investigation teams who face staffing shortages.

“My observations working at both the federal level for the Department of Justice and at the local government level suggest we don't assign our best to doing background and security clearance checks, and that's a long-standing thing. The best agents and investigators did not get into the field to do background investigations,” Ferguson said. “Couple that with the fact that when there's bandwidth and resource issues, and as important as this realm can be, it doesn't go to core day-to-day mission-related operations."

Ferguson continued, “It's a risk, and it needs to be monitored, and it needs to be maintained in consciousness because, at the end of the day, if something is important enough to require security clearances, then it's important enough to invest the resources necessary to do it right.”

Vetting questionnaire changes aim to broaden the talent pool

Across the entire government, skill gaps for the nation’s employees has long been a considered high-risk concern by the GAO since 2001. As the government seeks to broaden its talent pool, it has prompted changes to Standard Form 86.

Making questions on the form more inclusive has encouraged more people to apply for jobs in the intelligence community, especially when they might have perceived something in their background as a disqualifier from even applying, Frownfelter said.

For instance, Charlie Sowell, CEO of IT government contractor SE&M Solutions LLC and former deputy assistant director for special security at the Office of the Director of National Intelligence, was a part of the team in 2013 that changed how the form’s Section 21 framed mental health and sexual assault and its questions around seeking counseling.

“We changed it because … there was this myth out there that if you said you had a mental health problem, you were going to have your clearance yanked,” said Sowell, who is also a former Navy security officer. “Definitively, there are in the single digit number of cases each year where a person's clearance is revoked solely because of a mental health issue.”

The Department of Defense has made a concerted effort to accommodate people who might experience post-traumatic stress disorder, and the Office of the Director of National Intelligence has emphasized the importance of intelligence community members taking care of their mental wellbeing, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, Frownfelter said.

The Pentagon in Arlington, Va., near Washington, D.C. Photo by SpaceImaging.com/Getty Images

The Pentagon in Arlington, Va., near Washington, D.C. Photo by SpaceImaging.com/Getty Images“We really made a big push like, ‘Hey, if you're seeking counseling due to stress because the entire world is experiencing [the pandemic], we don't want you to think that this is going to disqualify you from staying in the intelligence community or applying to the intelligence community,” said Dean Boyd, chief communications executive at the National Counterintelligence and Security Center at the Office of the Director of National Intelligence.

Past drug use is another area of Standard Form 86 under evaluation.

Currently, the form asks about an applicant’s drug use during the past seven years. But the Office of Personnel Management took public comment earlier this year about significantly lowering the timeline — to 90 days — for past marijuana use, which is legal for recreational purposes in 23 states and DC.

The Office of Management and Budget is going through the process to change the question on Standard Form 86, Frownfelter said.

However, marijuana use is still federally illegal. Once an individual receives a national security position, they are expected to follow the federal laws around consumption, and they’re subject to drug tests, too, Boyd said.

“These changes were proposed in recognition of changing societal norms and the legal landscape at the state level regarding marijuana use,” Tran said.

The Office of Personnel Management expects these changes on the form “may improve the pool of applicants for federal employee and federal contractor positions,” Tran said.

An April 2023 report from ClearanceJobs, a network for professionals with federal government security clearances, surveyed young people ages 18 to 30 and found that 40 percent had used marijuana in the past year. Thirty percent had either withdrawn an application or not applied for a job based on the government’s policies on marijuana use for people seeking clearances.

ALSO READ: Two bloodthirsty extremists are accused of the same murder, but one won't face trial — here's why

“Marijuana use might be legal where they live now, but when they report it on the form, different agencies will apply that information differently for different positions, so it's never quite clear to individuals whether marijuana use is going to be a disqualifier,” said Valerie Smith Boyd, director of the Center for Presidential Transition at the nonprofit Partnership for Public Service. “Very often, it has been, despite it being legal where people live.”

“There’s a really dramatic change in the scope of questioning, looking for examination of marijuana use,” Smith Boyd continued. “Our organization thinks there is more that can be done to create a standard adjudication across the federal government, so that applicants really can predict what behavior is going to be allowable for what positions and when, so this is really a step in the right direction.”

The national security workforce is aging, too, which is why some of these changes to the investigation form have been proposed in order to encourage more young talent to work in the intelligence community.

Just 6 percent of the intelligence community is under 20, and 20 percent are under 40, ClearanceJobs reported. Those with more than 10 years of experience account for more than 70 percent of security professionals surveyed in a 2023 report on facility security officers working for the government and government contractors.

“The graying of those of the workforce, that's incredibly important to us too that the federal government overall is hiring young talent with enthusiasm to fix the problems in the country and the world,” Smith Boyd said.

The former State Department employee that Raw Story spoke with said military and government recruitment is low, which is a problem for attracting young people to national security careers.

“We are in the era of strategic competition coming out of post-9/11,” the former State Department employee said. “The old-school way of doing things is not working. China is a big deal, and a lot of Chinese Americans mean well and can make a difference and be trusted, but there’s still bias toward them. A lot are young.”

Are more leaks to come?

Many national security experts agree complete risk elimination isn’t realistic.

There will, undoubtedly, be another national security leak.

And the movie “Minority Report,” with its crime clairvoyant “precog” characters, is just that — a work of fiction. Even under the best of circumstances, it’s virtually impossible for the U.S. security apparatus to predict, with complete accuracy, who will commit a future violent or compromising act.

That doesn’t mean the government shouldn’t constantly strive to improve its capabilities.

“The good news is the vetting program has been hugely effective in tracking what it is designed to track,” said Lindy Kyzer, director of content at ClearanceJobs. “We talk about risk reduction and risk mitigation. There is never going to be risk elimination. We're not going to go full Minority Report.”

But Sowell says with certainty — “absolutely, 100 percent” — that the U.S. government will continue to see more people compromise national security and classified information.

“The clearance process isn't created to identify who's going to be a spy in the future. That is such a difficult thing to predict. We're going to have more of them like the kid in the Massachusetts Air National Guard,” said Thomas Langer, retired vice president of security for BAE Systems, one of the government’s largest aerospace contractors, and principal at industrial security consultancy, Atlantic Security Advisors.

Extremists in particular pose the biggest threat to protecting national security, Goldsmith said.

“Leaks can be a weapon,” Goldsmith said. “The neo-Nazis are always looking to sabotage infrastructure, and sharing information publicly or with the nation's adversaries or terrorist groups can lead to deaths on the battlefield and deaths right here in the United States.”

When determining national security protocols for the future, government agencies struggle to find the right mix of policies and openness. It’s a balance of improving processes to detect and prevent leaks, but “we also don't want to overcorrect and create unnecessary information stove pipes that could be detrimental to our ability to do our job as the intelligence community,” Boyd said.

“We don't want to go back to pre-9/11 days where people aren't sharing information that's needed, so we're just trying to keep that balance there,” Boyd said.

Experts agree Trusted Workforce 2.0 has made major steps in addressing problems that have plagued the security clearance process for years — from reducing backlogs to streamlining processes — but with such a major overhaul, the system will be a work in progress for years to come.

“We'd say there's been a lot of progress achieved but still a lot of more work to do,” Boyd said.

“Losing Track” is a three-part Raw Story series investigating problems lurking within the U.S. government’s security clearance system. Read Part I and Part II.

From Your Site Articles

Related Articles Around the Web

The Rushingbrook Children's Choir poses in the National Statuary Hall where they performed the National Anthem in May. A video of their performance being cut short went viral. Photo courtesy of David Rasbach

The Rushingbrook Children's Choir poses in the National Statuary Hall where they performed the National Anthem in May. A video of their performance being cut short went viral. Photo courtesy of David Rasbach Then-President Donald Trump sings the National Anthem during a wreath-laying ceremony at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier at Arlington National Cemetery on Memorial Day, May 29, 2017 in Arlington, Va. Photo by Olivier Douliery - Pool/Getty Images

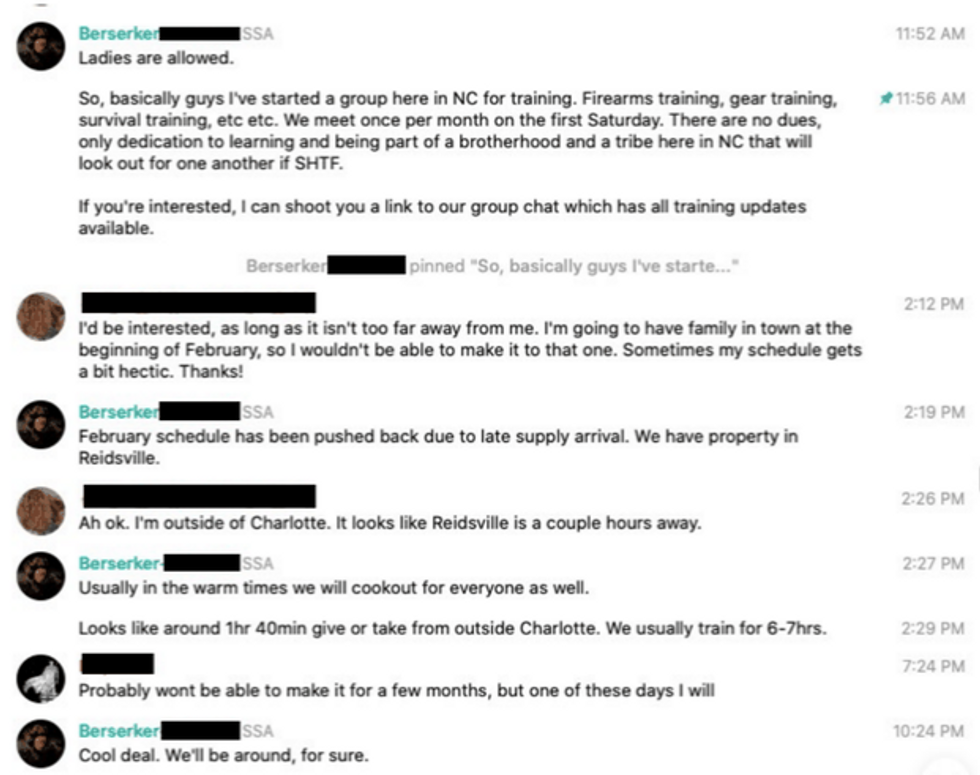

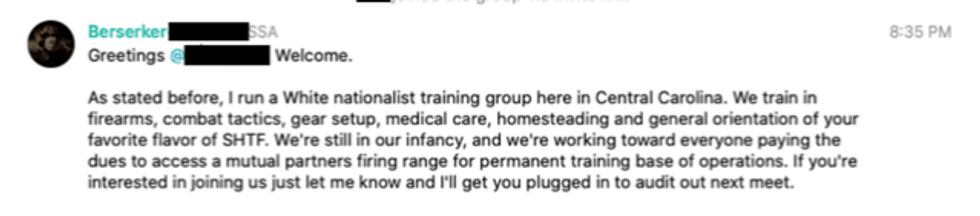

Then-President Donald Trump sings the National Anthem during a wreath-laying ceremony at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier at Arlington National Cemetery on Memorial Day, May 29, 2017 in Arlington, Va. Photo by Olivier Douliery - Pool/Getty Images Christopher Woodall, posting under the screen name "Berserker," invites white nationalists to a join a paramilitary training group in central North Carolina in January 2023.Telegram screengrab

Christopher Woodall, posting under the screen name "Berserker," invites white nationalists to a join a paramilitary training group in central North Carolina in January 2023.Telegram screengrab Message posted by Christopher Woodall in a Telegram channel in March 2023Telegram screengrab

Message posted by Christopher Woodall in a Telegram channel in March 2023Telegram screengrab A man receives a sign for Robert F. Kennedy Jr. before his official announcement that he is running for President on April 19, 2023 in Boston, Mass. Scott Eisen/Getty Images

A man receives a sign for Robert F. Kennedy Jr. before his official announcement that he is running for President on April 19, 2023 in Boston, Mass. Scott Eisen/Getty Images Jenny Oakley and Zeus, her family's Doberman. Doug McSchooler /

Jenny Oakley and Zeus, her family's Doberman. Doug McSchooler /  A pastor led a prayer before a school board meeting at Martinsville High School the week after Fox News aired a story about Accuracy in Media video featuring a local school administrator. He invoked the gospel of John to love one another. Photo: Stacey Miers

A pastor led a prayer before a school board meeting at Martinsville High School the week after Fox News aired a story about Accuracy in Media video featuring a local school administrator. He invoked the gospel of John to love one another. Photo: Stacey Miers Rep. Kathy Manning (D-N.C.) appears to have violated the STOCK Act again by failing to disclose a stock purchase for more than a year. Anna Moneymaker/Getty Images

Rep. Kathy Manning (D-N.C.) appears to have violated the STOCK Act again by failing to disclose a stock purchase for more than a year. Anna Moneymaker/Getty Images Source: The Citadel emails obtained through a South Carolina Freedom of Information Act request.

Source: The Citadel emails obtained through a South Carolina Freedom of Information Act request. Source: The Citadel emails obtained through a South Carolina Freedom of Information Act request.

Source: The Citadel emails obtained through a South Carolina Freedom of Information Act request. Incoming freshman march at The Citadel, The Military College of South Carolina on August 19, 2013 in Charleston, South Carolina. The Citadel, which began in 1842, has about 2,300 undergraduate students. Richard Ellis/Getty Images

Incoming freshman march at The Citadel, The Military College of South Carolina on August 19, 2013 in Charleston, South Carolina. The Citadel, which began in 1842, has about 2,300 undergraduate students. Richard Ellis/Getty Images Rudy Giuliani signs and autograph for The Citadel graduate Creighton Nash after the graduation ceremony on May 5, 2007, in Charleston, S.C. Stephen Morton/Getty Images

Rudy Giuliani signs and autograph for The Citadel graduate Creighton Nash after the graduation ceremony on May 5, 2007, in Charleston, S.C. Stephen Morton/Getty Images Rep. James Clyburn (D-SC) speaks during a dedication ceremony for a new statue of Pierre L'Enfant at the U.S. Capitol on February 28, 2022. Pierre L'Enfant was a French-American military engineer who designed the initial urban plan for Washington, DC. (Photo by Drew Angerer/Getty Images)

Rep. James Clyburn (D-SC) speaks during a dedication ceremony for a new statue of Pierre L'Enfant at the U.S. Capitol on February 28, 2022. Pierre L'Enfant was a French-American military engineer who designed the initial urban plan for Washington, DC. (Photo by Drew Angerer/Getty Images) Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene (R-GA). Flickr/Gage Skidmore

Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene (R-GA). Flickr/Gage Skidmore Chuck Grassley jumps ship: Joe Biden should have access to classified briefingsSen. Chuck Grassley (R-IA). Andrew Harnik / POOL / AFP

Chuck Grassley jumps ship: Joe Biden should have access to classified briefingsSen. Chuck Grassley (R-IA). Andrew Harnik / POOL / AFP Trump mob at the Capitol. Shutterstock

Trump mob at the Capitol. Shutterstock Rudy Giuliani, Donald Trump. Photo via AFP.

Rudy Giuliani, Donald Trump. Photo via AFP. Rudy Giuliani. Screengrab.

Rudy Giuliani. Screengrab. Then-President Donald

Then-President Donald  Chris Christie presidential rerun will pay residualsFormer New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie is one of the 2024 Republican presidential candidates to directly criticize Donald Trump. Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images

Chris Christie presidential rerun will pay residualsFormer New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie is one of the 2024 Republican presidential candidates to directly criticize Donald Trump. Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images Then-Rep. Ron DeSantis (R-FL) addresses a crowd while President Donald Trump watches at a rally in Tampa, Fla., on July 31, 2018.Photo: jctabb/Shutterstock

Then-Rep. Ron DeSantis (R-FL) addresses a crowd while President Donald Trump watches at a rally in Tampa, Fla., on July 31, 2018.Photo: jctabb/Shutterstock Former President Donald Trump (R) watches Republican candidate for governor Kari Lake speak at a ‘Save America’ rally in support of Arizona GOP candidates on July 22, 2022 in Prescott Valley, Arizona.(Photo by Mario Tama/Getty Images)

Former President Donald Trump (R) watches Republican candidate for governor Kari Lake speak at a ‘Save America’ rally in support of Arizona GOP candidates on July 22, 2022 in Prescott Valley, Arizona.(Photo by Mario Tama/Getty Images) Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene (R-GA) speaks during a Bikers for Trump campaign event held at the Crazy Acres Bar & Grill on May 20, 2022 in Plainville, Georgia. Joe Raedle/Getty Images

Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene (R-GA) speaks during a Bikers for Trump campaign event held at the Crazy Acres Bar & Grill on May 20, 2022 in Plainville, Georgia. Joe Raedle/Getty Images LinkedIn photo of Jordan Duncan, a Marine Corps veteran whom the government alleges had classified military materials on his hard drive.

LinkedIn photo of Jordan Duncan, a Marine Corps veteran whom the government alleges had classified military materials on his hard drive. The Pentagon in Arlington, Va., near Washington, D.C. Photo by SpaceImaging.com/Getty Images

The Pentagon in Arlington, Va., near Washington, D.C. Photo by SpaceImaging.com/Getty Images